South Asian Sikhs have a flourishing diaspora and a territorial homeland. Around 26 million Sikhs live worldwide, with 23 million in India, less than 2% of the 1.4 billion people. Punjab is home to 18 million (78%) of them, 58% of its population. Since Sikhs do not have a state, they are regarded as an ethno-religious community, not a nation. From 1984 through 1992, militant Sikh organizations launched a ‘war of national self-determination’ against the ‘secular’ Indian state ruled by the INC and the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, which conservative estimates estimate cost over 30,000 lives. Despite the long-standing electoral alliance between the dominant faction of the premier Sikh political party, the Shiromani Akali Dal (Badal), and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party in Punjab, the latter’s embrace of Hindutva and moves to consolidate political power after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s landslide electoral victory in 2019 have raised fears of a Hindu Rashtra (or Hindu state) in India, which could lead to a resurgence of Sikh

Statehood is the foundation of nationalism, even as globalization has changed collective identities. Most states claim to represent “nations,” but the two are not the same. Statehood is the monopolization of lawful force over territory, while nationhood is the ‘imagined community’ the state professes to represent. Therefore, most academic examinations of Sikhs have ignored their ethnonational characteristics, who have been examined almost solely as a ‘world religion’ like Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam since the Partition of the subcontinent. Gurharpal Singh and I argue in Sikh Nationalism that many Sikhs in Punjab and diaspora consider themselves a ‘nation.’ Focusing on the ‘inner dimension’ of Sikh subjectivity draws on and contributes to nationalism ideas. Sikh nationalism is a ‘derivative discourse’ of colonial modernity because it uses Western categories to describe Sikh collective identity, but it articulates a pre-existing sense of political community based on the Punjab Sikh peoples’ ‘sacred’ myths and memories. The Sikhs’ two discourses are connected because they follow a ‘world religion’ as a nation.

Guru Nanak (1469-1539) founded Sikhism, which is a “religious” community. Guru Nanak was followed by nine other gurus who institutionalized the new faith by introducing Gurmukhi (a Punjabi script) to write sacred scriptures in a Holy Book, the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, new sacred rituals, and the founding of Sri Harmandir Sahib (the Golden Temple) as the spiritual and the Akal Takht facing it as the temporal home of the community. This brought it into confrontation with the Mughal Empire, which tried to impose Islam on the Punjab and martyred several Gurus, leading to the Khalsa in 1699.

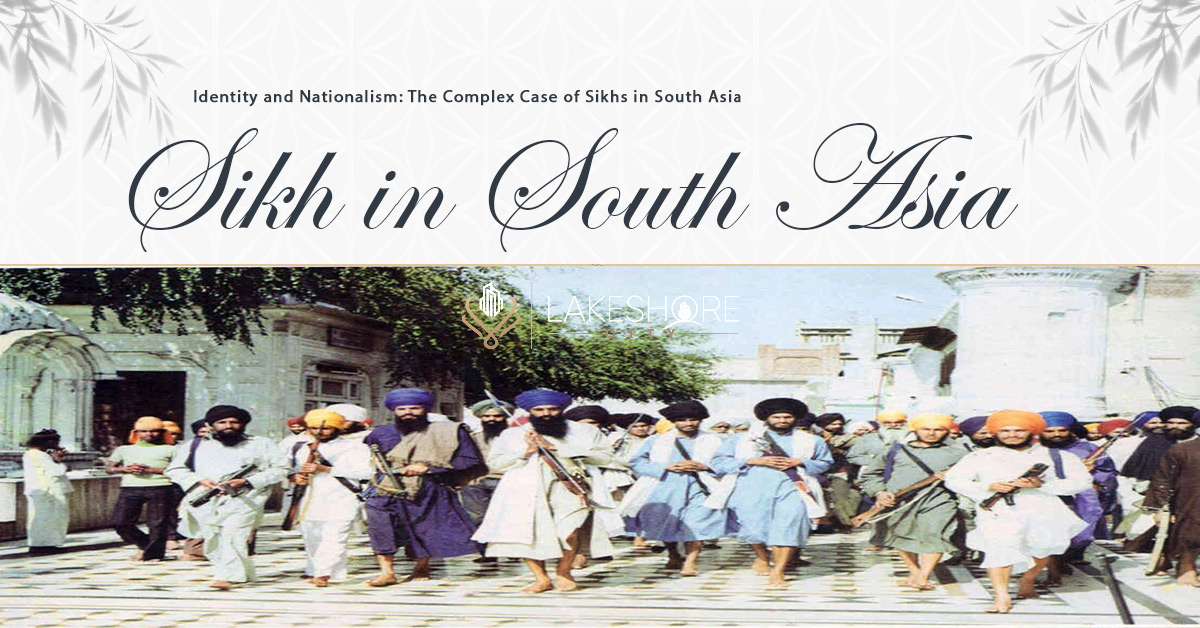

The 10th and final Guru, Gobind Singh (1658-1707), founded the Khalsa, or ‘community of the pure.’ Guru Gobind baptized his followers with five external symbols (5Ks)—kesh (unshorn hair), kacha (short drawers), kirpan (sword), and kanga (comb)—and renamed them Singhs (males) and Kaurs (females). The new initiates then baptized the guru. He subsequently gave spiritual authority to the Granth Sahib and temporal authority to the community of baptized Sikhs through Guru Panth, the corporate body of the Khalsa in which his soul is eternally present. This ushered in a new Sikh discourse: nationalism. As I have shown before, Guru Gobind Singh’s manifestation of sovereignty in the Khalsa, ‘the community of the pure’, was the modern Sikh ‘nation’ before colonial domination, making it vital to Sikh nationalism.

This challenges modernist and some postcolonial accounts of nationalism as a modern phenomenon, an ideology that accompanied state formation and capitalism in Western Europe after the French Revolution and was introduced to South Asia during colonialism. Post-colonial nationalism is derived from colonial discourses in the following ways: First, utilizing Western historical and political concepts of the ‘nation’ and ‘nationalism’, it articulates geo-cultural differences. Second, it mobilizes the ‘nation’ to seize state authority. In a later essay, Partha Chatterjee insightfully argues that the nation had a spiritual, sacred quality that the colonizer did not see. Western modernist nationalism confuses the spiritual domain of the ‘nation’ with the outward domain of the ‘state’. Anderson called the nation an ‘imagined community’, but its conception differed outside the West. The Sikhs’ ‘nation’ was the Khalsa Panth, their ‘religious’ community. Thus, modernist explanations that attribute the rise of Sikh nationalism in the last decades of the 20th century to the Green Revolution or the 1984 Indian troops’ storming of the Golden Temple complex, Sikhism’s holiest site, cannot explain the strength of nationalism.

The late Anthony D. Smith called the ‘nation’ a ‘sacred communion of the people’ dedicated to ‘the cult of authenticity and the values of national autonomy, unity, and identity in a historic homeland’. His recognition of the spiritual side of nationalism helps explain the strength of nationalist sentiment among Sikhs and much of the globe in an age of globalization, despite the distinctly Christian imagery associated with ‘communion’.

Our Featured Article:

Read More: Pakistan’s International Gandhara Symposium | Buddhist Tourism

Don’t miss the chance to invest with Lakeshore! Secure your investment today by investing your financial investment with Lakeshore in the following available options like Lakeshore City, Lakeshore Club, and Lakeshore Farms.

For More updates, please Contact +92 335 7775253 or visit our website https://lakeshorecity.com/

Lakeshore City is the upcoming elite lifestyle at Khanpur Dam. Offering no parallel amenities for the members and owners of distinguished farmhouses.

Become Part of Luxurious Lifestyle

Contact: 0335 7775253